Posted:

15 Aug 2019

This is a guest post by the Archive’s summer intern this year, Kate Foxton.

One of the treasures of the archive is the diary of fellow commoner Spencer Penrice for the year 1736-1737. Born in August 1719 to a wealthy landed family from Hertfordshire, Spencer was admitted to Trinity Hall on the 29th June 1736. His father, Sir Henry Penrice, was a judge of the High Court of Admiralty and ex-fellow of the college. The status of fellow commoner was reserved for wealthy, often noble, students who were charged higher fees and not required to proceed to a degree. Following in his father’s footsteps, Spencer began his first term at Trinity Hall on the 18th October when, after travelling up from the family’s seat at Offley, he was greeted by fellow and Regius Professor of Law, Dr Dickins, and dined with him at the Rose Inn. From this point on, the diary meticulously records daily student life in hourly increments. Although its tone is ‘more of dutiful record than self-conscious introspection’[i] it nevertheless provides a fascinating insight into the social, academic and religious life of a fellow commoner in the early eighteenth century.

The College Community

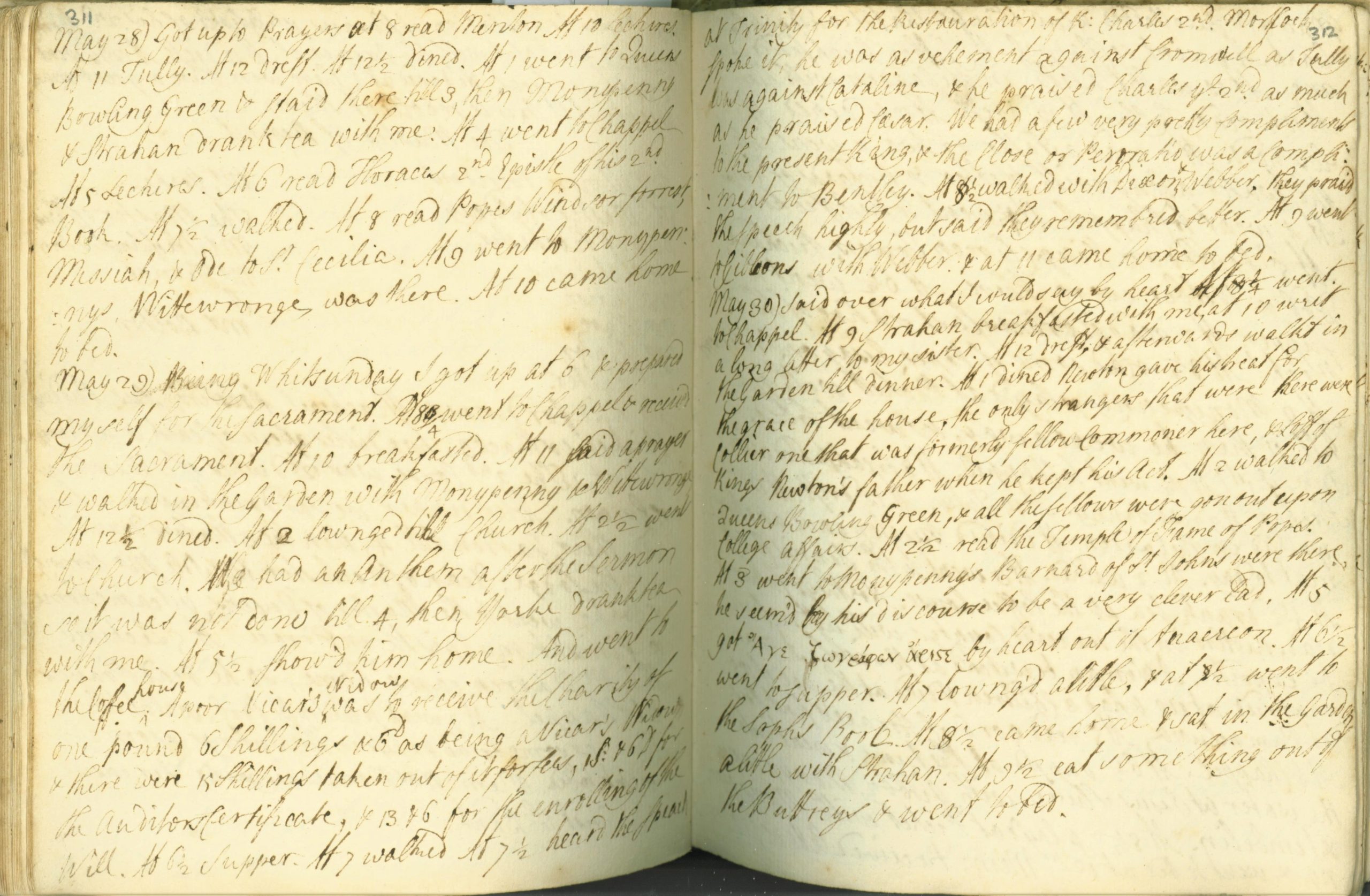

What is apparent from Spencer’s diary is the existence of a rich and active social life within the college. He is never short of company when he takes time away from his studies to breakfast, dine in commons, take tea in his room or walk in the gardens. He often stays in his friend’s chambers late into the evening playing piquet, whist, brag or quadrille. He attends debates in the Hall (Nov 22nd, ‘Gibbon kept the Act, & Grimes & Strahan opposed him’) and is involved with the college Music Club, recalling a memorable meeting on April 27th when ‘we had some French Horns’. More active pursuits include tennis or, in the summer months, bowls at Queens Bowling Green and swims in the ‘Sophs Pool’. Occasionally he seeks a little respite from his enthusiastic companions, noting on the 3rd May that ‘Northey came into my Room, & staid till 5 ½ so I walked in the garden to get rid of him’. Although the majority of Spencer’s social and academic life is centred within the college, he participates in a wider community of undergraduates. On May 29th he attends a debate for ‘for the Restoration of K: Charles 2nd’ at Trinity College and notes that one speaker ‘was as vehement against Cromwell as Tully against Cataline & he praised Charles ye 2nd as much as he praised Caesar’.

THPP/PEN p. 311-312, debate at Trinity College.

A man about town

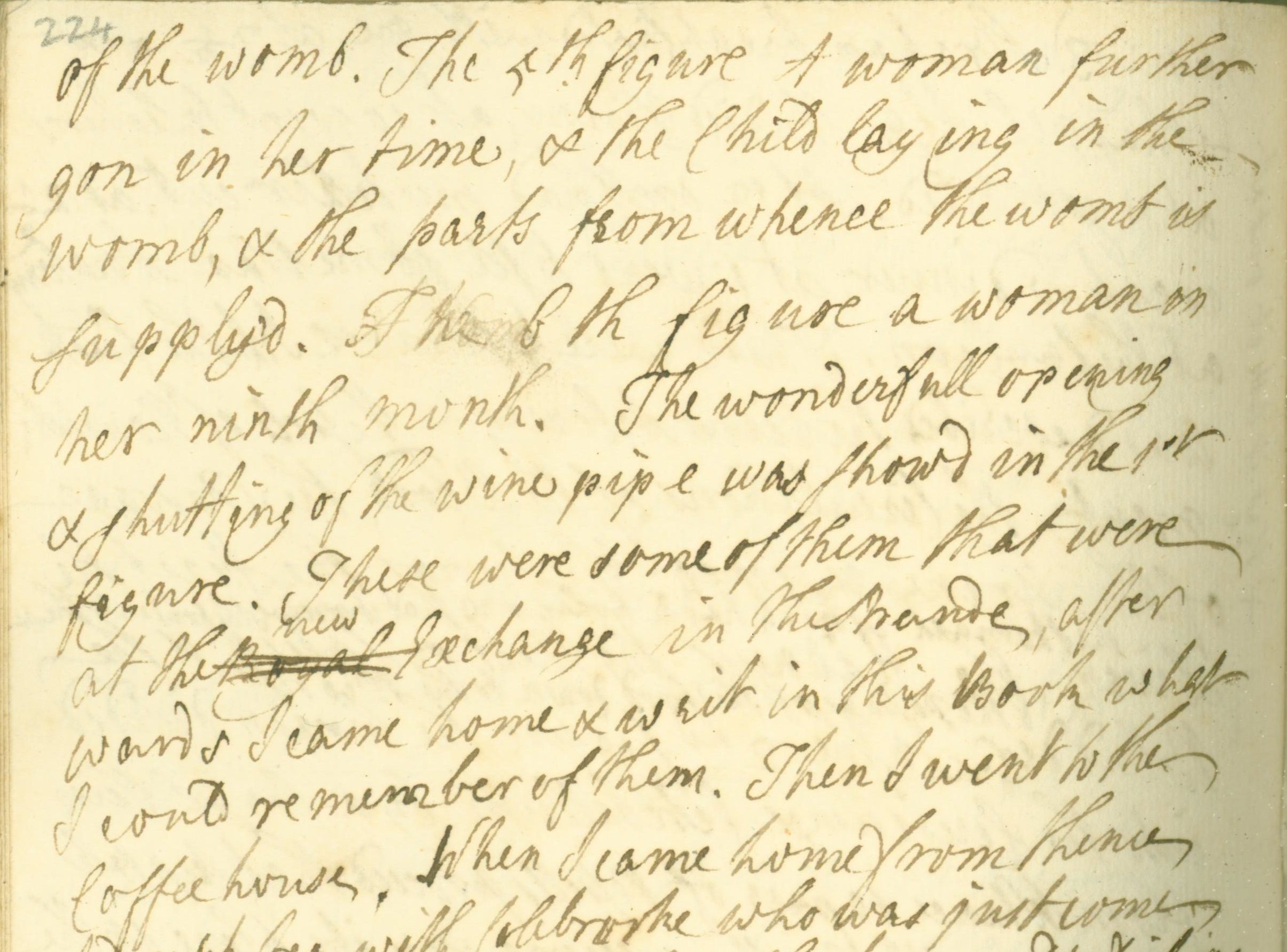

Spectacles in the town provided exciting distractions from study. On March 13th, Spencer watches bull baiting in Parker’s Piece; on the 15th he notes, somewhat ominously, that he went ‘to the Castle Hill to see the Prisoners hang’d but was too late’. On Jan 13th he recalls seeing a display of Wax Anatomy at the ‘Faulcon’. This fascinates him, and he describes each of the five figures displayed in precise detail, including the figure of ‘a woman just growing big & the situation of the womb’. Such displays were common across Europe in this period, and showmen often took wax cabinets on the road.[i] It is striking that these models, clearly of interest as scientific teaching tools as well as spectacles, are not confined to the environs of the university but displayed in an Inn and accessible to a more general public.

THPP/PEN p. 224, wax anatomy at ‘The Faulcon.’

The Life of a lounger?

Fellow commoners had a reputation for being ‘loungers’ who spent their time hunting, dancing and wiling away the afternoons in coffee houses rather than applying themselves to serious study.[i] The life of a ‘lounger’ is depicted in a humorous poem of 1751 from The Student or Oxford and Cambridge Monthly Miscellany II:

I rise about nine, get to breakfast by ten

Blow a tune on my Flute, or perhaps make a Bow;

Read a play till eleven, or cock my lac’d hat,

Then step to my Neighb’rs till Dinner to chat.

Dinner over, to Tom’s or to Clapham’s I go

The news of the town so impatient to know;

…

From the coffee-house then to Tennis away,

And at six I post back to my college, to pray:

I sup before eight, and secure from all duns,

Undauntedly march to the Mitre or Tuns….

The phenomenon of the ‘lounger’ appears in a letter of 1767 from undergraduate Framingham Willis to Thomas Kerrich, a student coming up to Cambridge for his first term.[ii] Willis warns Kerrich to beware the ‘interruption of Loungers’ who ‘take a pleasure in ruining two hours in a morning by idle chit-chat’. There are certainly shades of this leisurely, privileged lifestyle in Spencer’s journal. Feb 17th is more than a little reminiscent of the poem:

I breakfasted with Strahan. At 7 ½ went to Chappel. At 8 read Vinny. At 10 went to Lectures. At 11 read Vinny. At 12 drest. At 12 ½ went to dinner. At 1 read part of a play in Gibbon’s Room. At 2 writ a letter to Lee. At 3 Howard & Spence came & drank tea with me. At 5 they went away & I went to Lectures. At 6 went to Chappel. At 6 ½ set my things to rights, & went to the Coffee house. At 8 Brown, Brand, Sir J Cust, Powlett, & Colebrooke came & play’d at Hands here, & staid till 12 ½, & then I went to bed.

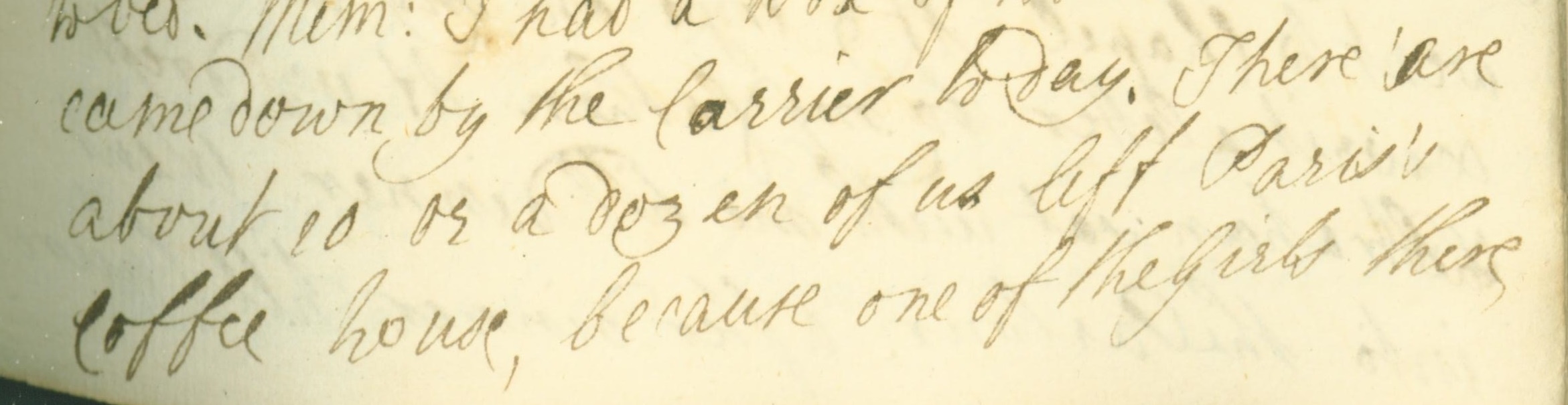

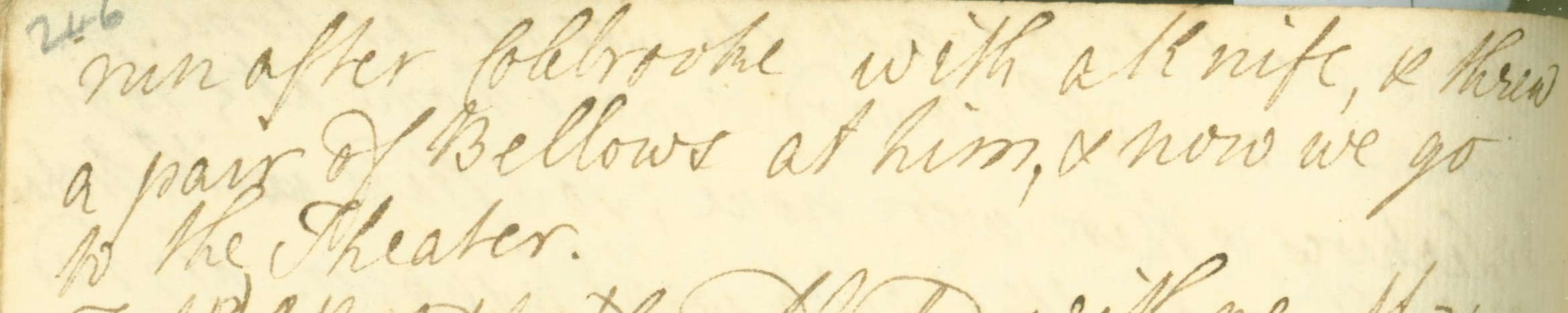

Coffee houses were established spaces of socialization in England by this period. There were at least eight or nine in existence around Cambridge by the mid-18th century and Spencer frequents them with satisfying regularity. Recent archaeological findings suggest that the ‘Claphams’ mentioned above was situated on All Saints Passage, although the earliest surviving record is the victualling licence afforded to William Clapham in 1748 so perhaps a little late for Spencer.[iii] Indeed, Spencer names a coffee house only once – Paris’s. At the coffee house Spencer picks up the ‘news of the town’. This varies from the political (22nd May, ‘everybody will be entitled to the Benefits of the Insolvent Debtors Bill’) to the botanical (June 3rd, ‘a famous plant has blown & bears fruit in Holland’) to the supernatural (June 1st, ‘a woman bewitched at Bristol’) to the purely salacious (June 26th, ‘a man the very morning before he was married to a great Fortune, had the misfortune to have a letter from her to desire to be excused’). On one occasion, the coffee house itself becomes a stage for scandal when ‘one of the girls’ at Paris’s ‘ran after Colebrooke with a knife, & threw a pair of Bellows at him’.

THPP/PEN p. 245-246, scandal at the Coffee House.

Although he certainly lives a privileged lifestyle as a fellow commoner, it seems unduly harsh to dub Penrice a ‘lounger’. He undertakes courses in mathematics, classics and astronomy but focuses the majority of his time on law. He takes his academic commitments seriously, reading Vinny’s Legal Commentaries and undertaking mathematical problems daily, and his attendance at lectures are as regular as his afternoon trips to the coffee house. A typical day more closely resembles Nov 11th:

‘I went to chapel breakfasted with Colebrooke. I studied Vinny from 9 to 10 then went to lectures till 12 and afterwards compared Wood’s Institutes with Parry’s. Dressed for dinner. Afterwards I took a little walk & came in & read a little of Corvinus till Sir J:Cust & Pilk Hale came, they staid till 4, then I went to Logick, & from thence to Puffendorf, & then to chapel & supper, & from thence to the Coffee house. I came home about 8 read Vinny till 9, when I could hardly keep my Eyes open, so I studied mathematics till 10, then went to bed’.

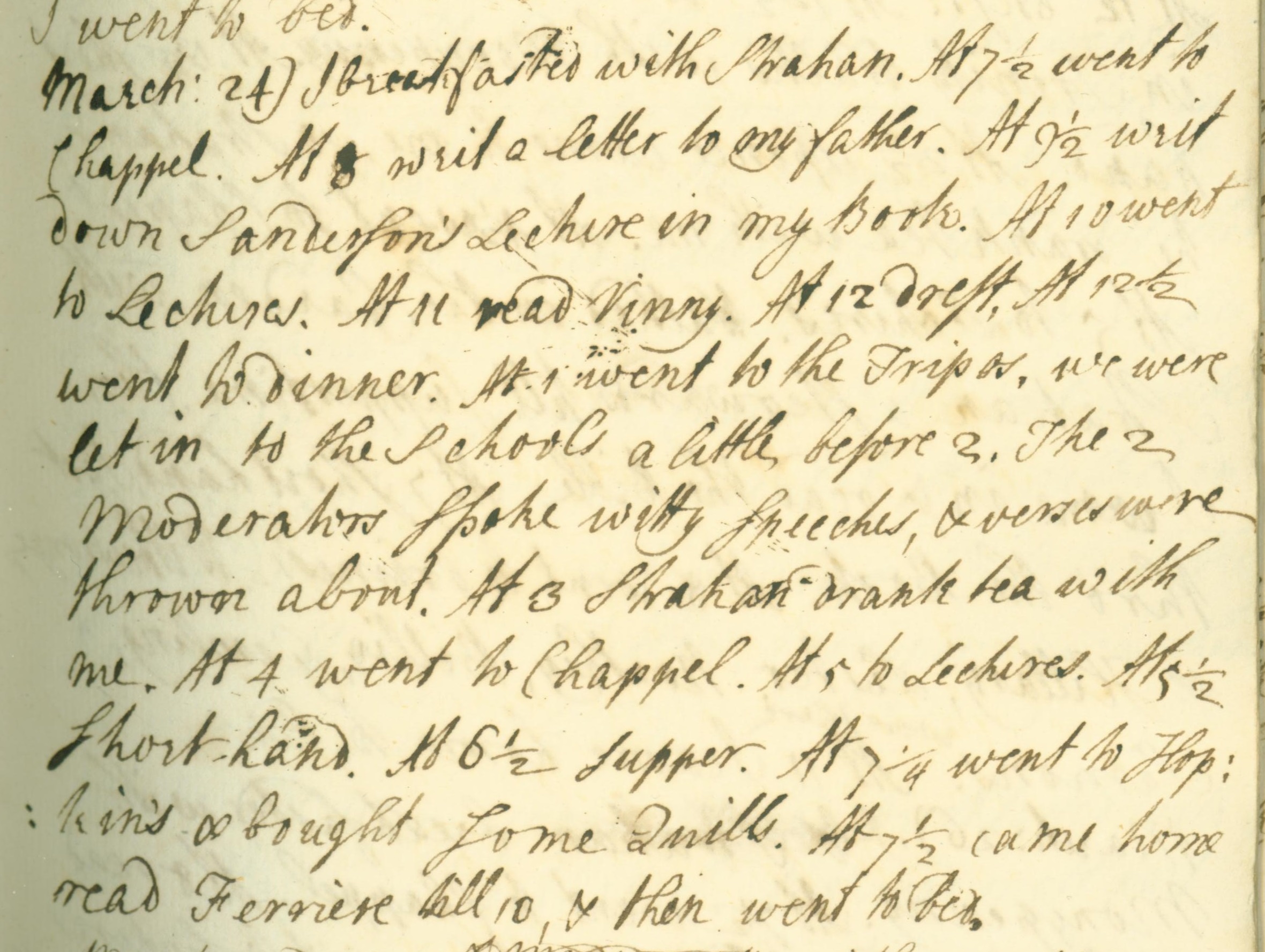

Indeed, Spencer seems to suffer just as much from the irritating interruptions of ‘Loungers’ as Willis, noting on Nov 24th that he went to his room ‘with an intent to study, but Colebrooke came & took me to his Room where I read part of a play’. Although his academic life sounds just as strenuous as any undergraduate today, Tripos sounds a lot more fun in the 18th century. Spencer notes on March 24th : ‘at 1 went to the Tripos, we were let in to the schools a little before 2, The 2 moderators spoke witty speeches, & verses were thrown about’. Unlike today, Tripos was not examined through a written examination but through oral disputation.

THPP/PEN p. 271, March 24th, Tripos

Tragically, Spencer died of small-pox on 6th January 1739, aged just 20 years old. We shall never know how serious his academic ambitions were, or whether he would have pursued a career in the college as his father had before him. The poignant family memorial in Great Offley Church describes him as ‘a youth of great virtues. And expectations’.

[i] Howes, Graham, ‘Eighteenth Century-Student Life – The Diary of Spencer Penrice’.

[ii]Maerker Anna, ‘Anatomizing the Trade: Designing and Marketing Anatomical Models as Medical Technologies, ca.1700-1900’ Technology and Culture, 54:3 (2013).

[iii] Stubbings, Franks, Bedders, Bulldogs & Bedells: A Cambridge Glossary Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1991) pp.47-48.

[iv]Venn, John, Early Collegiate Life (1913) pp.241-252.

[v] Cressford, Craig; Hall, Andy; Herring, Vicki; Newman, Richard, ‘”to Clapham’s I go”: a mid to late 18th-century Cambridge coffeehouse assemblage’ Post-Medieval Archaeology, 51:2 (2017).