Posted:

29 May 2019

The Old Library at Trinity Hall holds a very special French Renaissance book (H*.VI.68): Pierre Boaistuau, Histoires tragiques, extraictes de quelques fameux autheurs, Italiens & Latins, mises en françois […] Dediées à Tresillustre & Treschrestienne, Elizabet de Lenclastre, par la grace de Dieu Royne d’Angleterre (Paris: s.n., 1559)

Translated (with abridgements) from the Italian Matteo Bandello’s Novelle of 1554, Pierre Boaistuau’s Histoires tragiques fast became a bestseller after they appeared in 1559. In France they inaugurated an important subgenre of short narrative fiction, marked by sensational tales of forbidden love, the vicissitudes of fortune and vivid expressions of extreme pathos.

Over the subsequent fifty or so years a number of French writers, such as François de Belleforest, Vérité Habanc, Jacques Yver and François de Rosset all wrote ‘histoires tragiques’ for an enthusiastic market. In England especially, the Histoires tragiques enjoyed an illustrious afterlife: via some combination of Arthur Brooke’s verse adaptation and William Painter’s The Palace of Pleasure, one of Bandello-Boaistuau’s tales eventually became the source of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

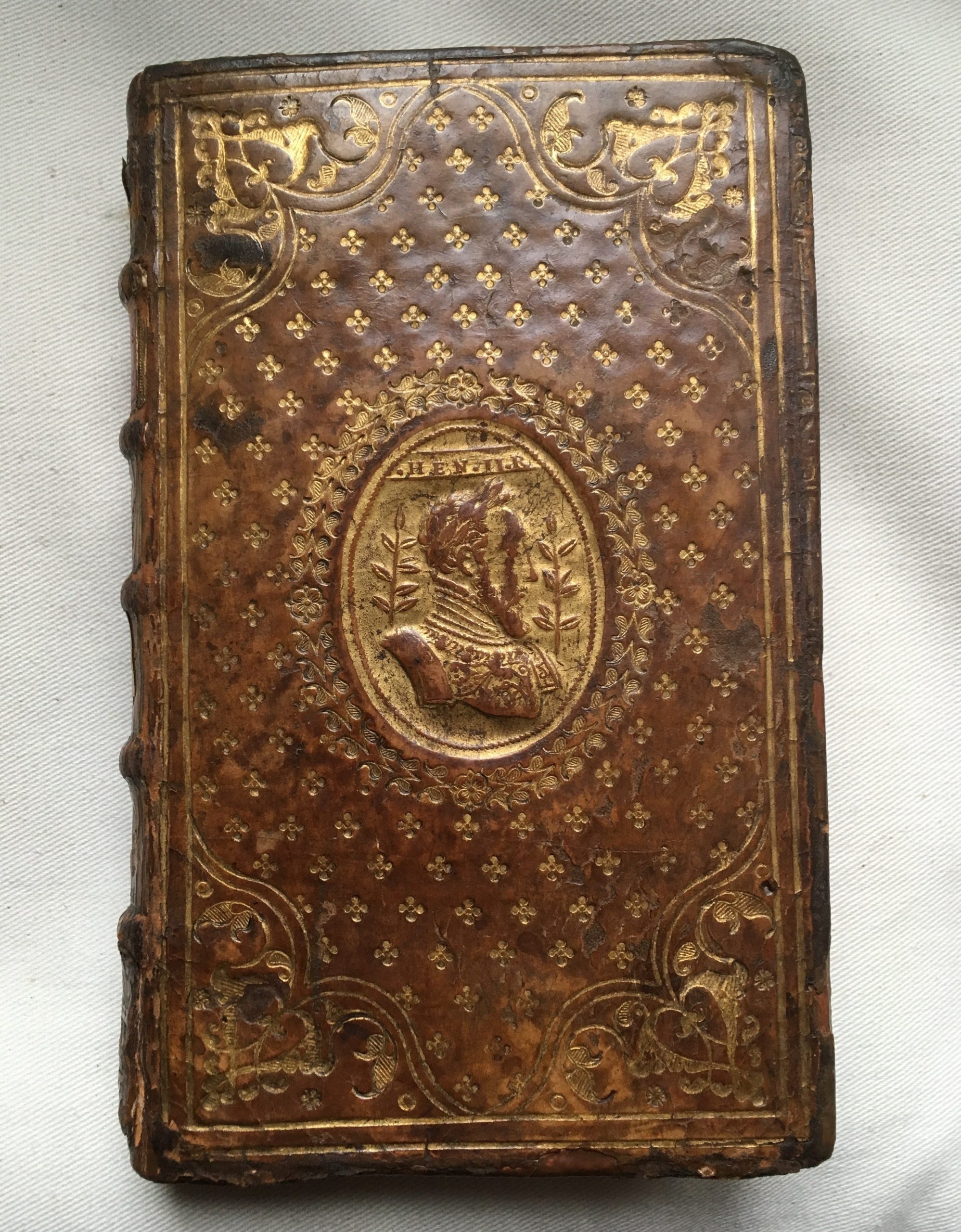

The Trinity Hall copy may mark an important staging post in Boaistuau’s English career. It is an exceptionally rare variant edition, especially dedicated to Elizabeth I and with certain disobliging references to English royalty removed. Only one other example of this variant survives (at the Folger Library, Washington). Unlike the relatively plain Folger volume, Trinity Hall’s is housed in an elegant-looking calf binding, centrally stamped with an oval gilt medallion featuring the profile of Henri II of France.

How did it reach England? We know that Boaistuau left France for England some time in 1559-1560. We also know that on arriving at the English court Boaistuau presented Elizabeth with a sumptuous manuscript version of another text, the Histoires prodigieuses, now held in the Wellcome Library, London (western MS 136). The Boaistuau scholar Stephen Bamforth, who first unearthed the Wellcome manuscript, has recently suggested that the Trinity Hall Histoires tragiques may have been a further gift to Elizabeth. His suggestion gains force from the presence in Cambridge of a third Boaistuau volume clearly intended for the Queen, the Institution du royaume chrestien (1560). Elegantly decorated with coloured initials and the English royal arms, this volume is now in Emmanuel College Special Collections (S16.4.12).

Binding, front, by Claude Picques and Etienne Delaune

Bamforth’s thesis of a royal presentation copy is certainly appealing. In the absence of the elaborate manuscript or decorative work that are features of the Wellcome and Emmanuel volumes, much depends on what we make of the Trinity Hall binding. Bamforth finds it ‘superb’. The gold ‘semé’ pattern and central gilt medallion undoubtedly convey an impression of luxury. Medal-stamped bindings had become fashionable in the late 1550s, an Italian feature that first reached the Parisian market via Lyon earlier that decade. The sense of a high-status object is enhanced by the identity of the binder, Claude Picques, whose profile of Henri II was designed by the prestigious engraver Etienne Delaune. Picques declares himself ‘royal binder’ (ligator Reg[is]) in the colophon to a Psalter also dated 1559, and certainly moved in distinguished circles: in 1568 his daughter is reported as having been treated for plague by no less than the royal physician Ambroise Paré. Though different in design, the bindings on the other Boaistuau volumes at the Wellcome and Emmanuel can probably also be attributed to Picques.

And yet some doubts remain. As Bamforth points out, the text itself is noticeably messy for a presentation volume. Even by the relatively lax standards of the period, it shows signs of hurried composition (in the multiple misspellings of ‘Lancaster’ as ‘Lenclastre’ or ‘l’enclastre’, for example). Furthermore, the binding itself, though attractive, is not rare: Anthony Hobson lists several variants of the Henri II medallion design, with as many as 47 examples still surviving. Despite its luxury appearance, it seems more likely to have been destined for trade bindings than for presentation copies. This is certainly the view of the book historian Eugénie Droz who (in a short article not cited by Bamforth) reports that whereas she could find no examples of such bindings belonging to Picques’ French royal patrons, she did locate one whose owner records having paid the binder the measly sum of ‘6 sous, 3 deniers’: hardly a suitable gift for a queen. Finally, there is a problem of chronology: the dedication to Elizabeth is dated 20th October 1559; Henri II had died on 10th July that year, from an injury received during a jousting accident. Why would Boaistuau have presented the new Queen of England with a book bearing the face of French king three months dead?

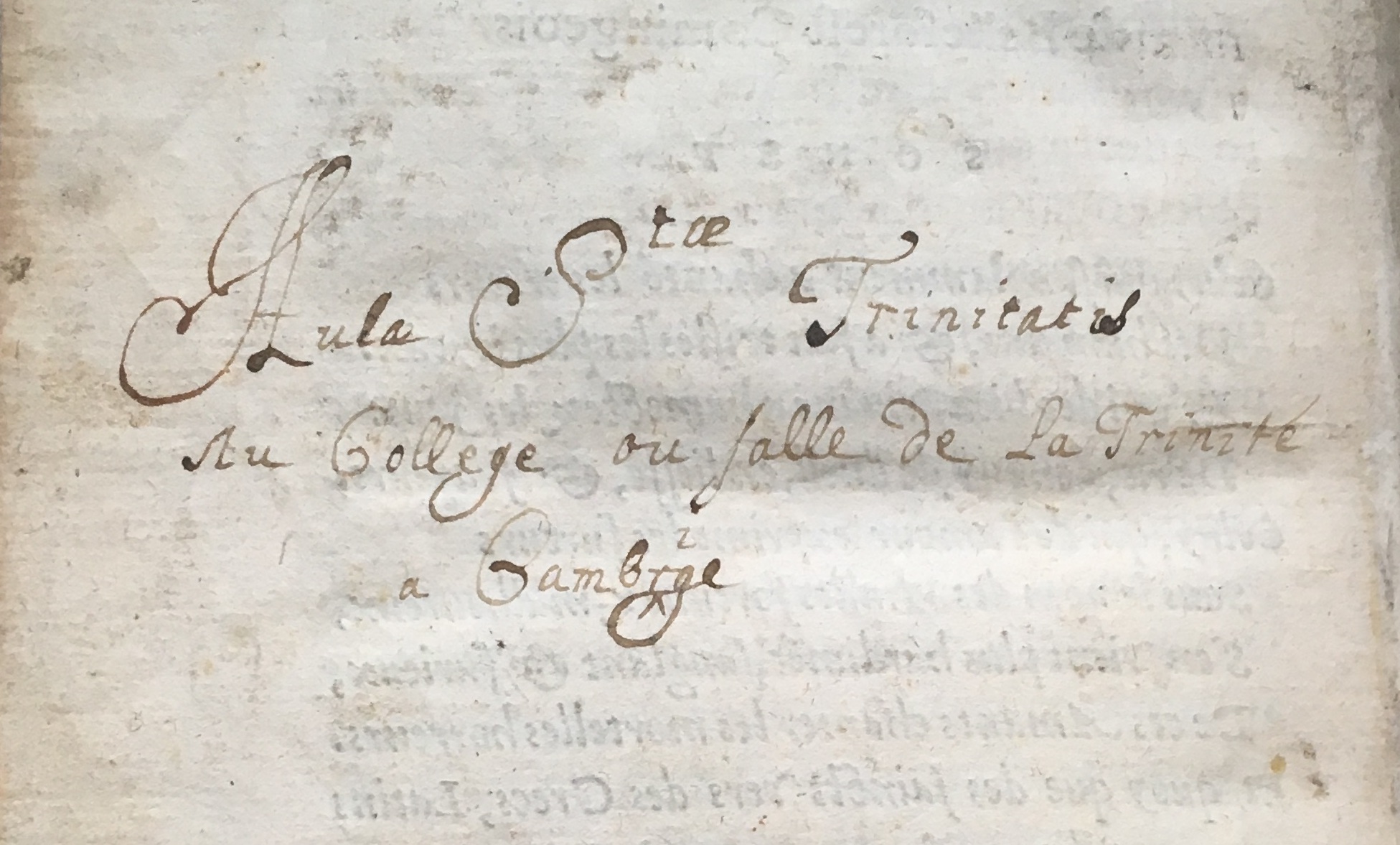

Whether or not the volume ever passed through Elizabeth’s hands, it eventually made it to Trinity Hall. A donation inscription on the rear flyleaf suggests that its early donor was indeed French, and even seems to have shared Boaistuau’s questionable grasp of the orthography of English place names: ‘Aula Stae Trinitatis. Au college ou salle de la Trinité a Cambrige [sic].’ Could this inscription be in Boaistuau’s hand, or that of his secretary? If so, what had Trinity Hall done to deserve such a boon?

Inscription on rear flyleaf

This is a guest post by Dr Tim Chesters, Clare College, Cambridge.

References

Stephen Bamforth, ‘Boaistuau, ses Histoires tragiques, et l’Angleterre’ in Les Histoires tragiques du XVIe siècle. Pierre Boaistuau et ses émules, ed. by Jean-Claude Arnould (Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2018), pp. 25-37

Eugénie Droz, ‘Les reliures à la médaille d’Henri II’, in Les Trésors des bibliothèques de France, vol. 4 (Paris: G. Van Oest, 1931), pp. 16-23

Eugénie Droz, ‘Prix d’une reliure à la médaille Henri II’, Humanisme et Renaissance 2.2 (1935), 175-76

Anthony Hobson, Humanists and Bookbinders: The Origins and Diffusion of the Humanistic Bookbinding 1459-1559 With a Census of Historiated Plaquette and Medallion Bindings of the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989)